Control in Stress | Upasana Shah

We often face stressful situations in daily life that require us to act on them. However, we have limited mental energy and cannot respond to every stressful event in the same way. Deciding when to put in effort may depend on how much control we have over a situation, i.e. whether our actions can change what happens next. Different parts of the brain help us deal with stress, but it is still unclear how these brain responses change when we feel more or less in control. To study this, we measure brain activity using fMRI while people perform a task that varies in control.

Interested in taking part in our study?

Send an email to stresscontrol.study@donders.ru.nl!

Neural mechanisms of working memory | Helena Olraun

Our research explores how the brain controls which information enters working memory (input gating) and which stored information is used to guide our actions (output gating). These gating processes help us stay focused and flexible in a rapidly changing world. Across multiple fMRI studies, from 3T to ultra-high-resolution 7T and most recently an innovative pharmacology-7T fMRI approach, we map these mechanisms from circuits to cortical layers, revealing how the brain keeps thought and behavior on track.

Want to know more? Check out our blogposts on what working memory gating is, how we can use high-resolution fMRI to zoom into the brain and its functions, and how dopamine helps to flexibly change our thoughts

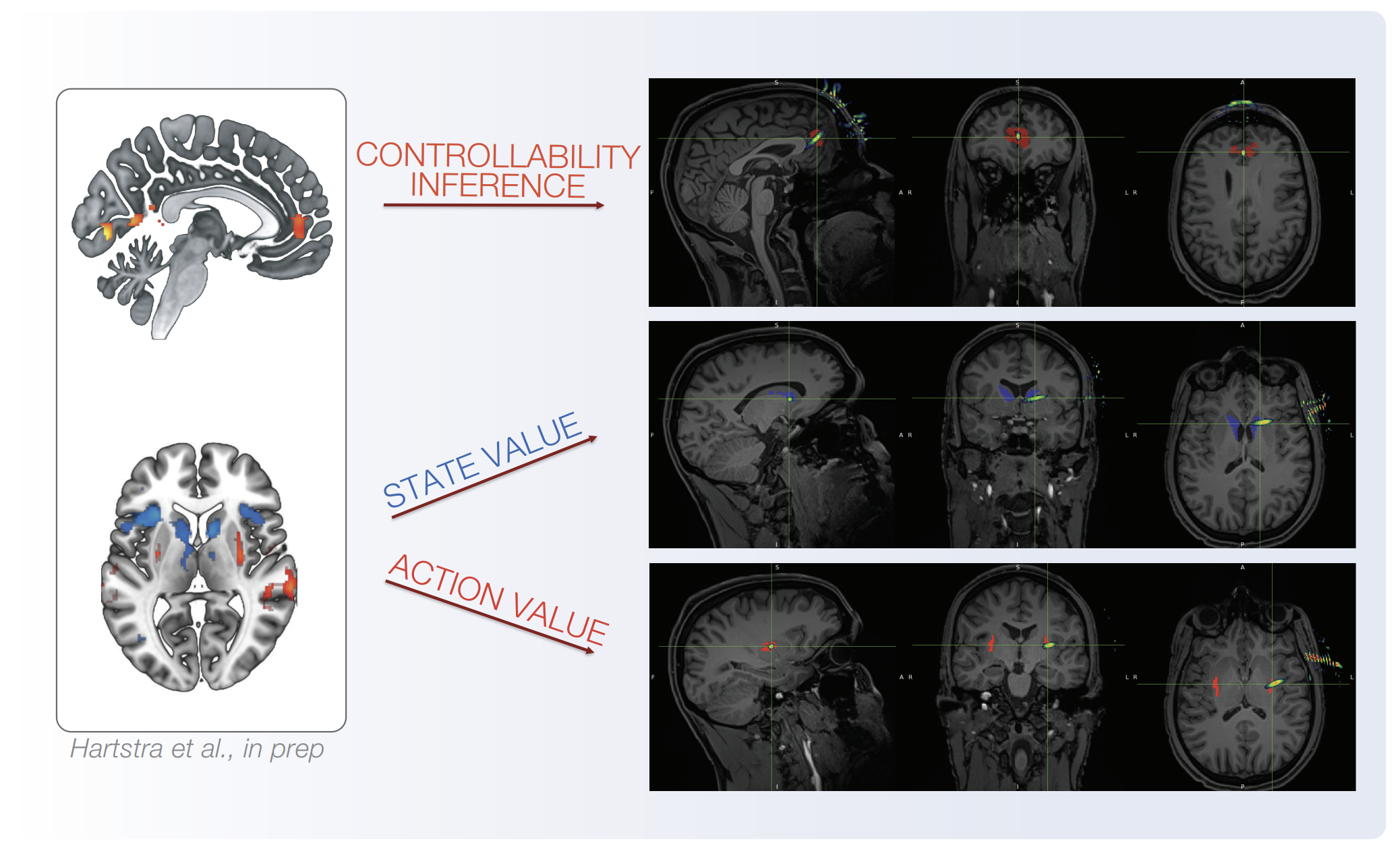

Neuromodulation of control beliefs | Marwan Engels

Depression is highly prevalent worldwide, and for about 30% of patients, treatments such as therapy or medication are insufficient. A key component of depression is learned helplessness, where prior stressful experiences shape our current belief that one’s actions have no effect on the situation. This can lead to maladaptive behavior, increased stress, and more rigid beliefs (e.g., stronger Pavlovian bias). The medial frontal cortex plays a crucial role in estimating controllability. In the ControlTUS project, we use transcranial ultrasound stimulation (TUS), a novel non-invasive brain stimulation technique, to modulate activity in this region and test its causal role in controllability inference (i.e., perceived control).

Offline replay of memory traces of creative narrative construction | Sajad Kahali

Our research investigates how the brain uses learned knowledge from past experiences to understand new situations and generalize what it has learned, such as forming original stories. When we rest, the brain “replays” patterns of activity linked to earlier experiences. This replay is not a simple replay of what we saw or heard, but a smart reorganization based on the deeper lessons we extracted. In other words, the brain remembers what was meaningful, not just the raw details. By reshaping past knowledge in this way, the brain may help us quickly make sense of new events and respond creatively.

Distract or accept to release ruminative thoughts – an fMRI study | Natalie Nielsen

Repeated overthinking about past events, known as rumination, is linked with increased activity in a brain network that is usually active during rest, called the default mode network. The present study examines whether two emotion-regulation strategies, i.e., a brief mindfulness exercise and distraction, can reduce rumination by influencing this overactive brain network. We expect mindfulness to have longer-lasting effects than distraction, because it helps people develop a meta-cognitive skill, that is to notice and guide thoughts more consciously. Instead, distraction is likely to provide only short-term relief as thoughts can easily return once the distraction is over.

The PRYME study - Promoting Resilience in Youth through Mindfulness mEditation | Maud Schepers

Internalizing problems such as anxiety, worry, and low mood are becoming more common in young people and may represent an early stage of serious mental illness development. The PRYME study examines whether mindfulness training can reduce these problems in help-seeking youth aged 16-25. In this randomized controlled trial, participants are assigned to either care-as-usual only or care-as-usual plus an 8-week mindfulness program involving meditation, mindful movement, and yoga. The study follows participants over 9 months and uses clinical measures, computer tasks and brain scans to investigate how mindfulness affects mental health problems and underlying cognitive and neural processes.

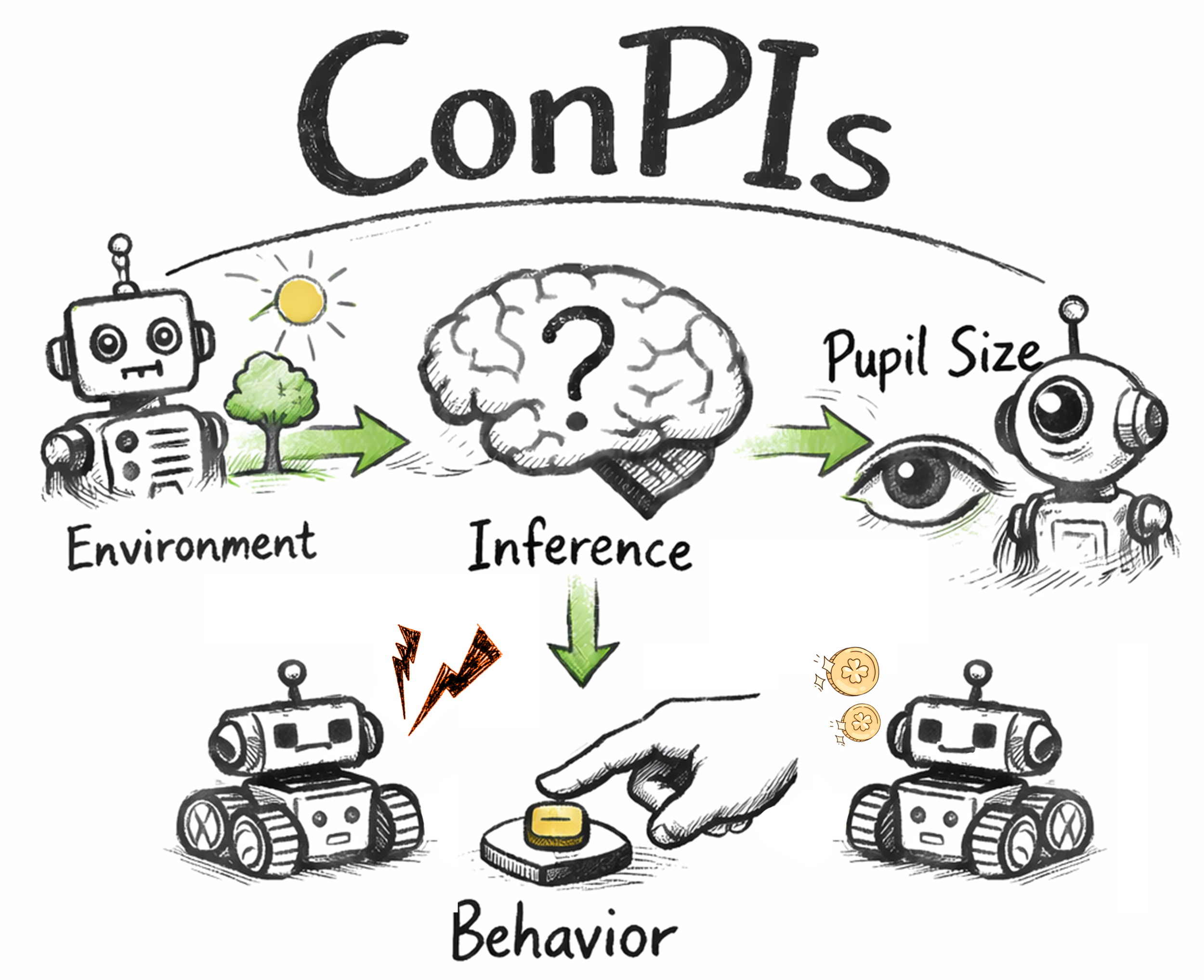

Anticipatory pupil dilation is enhanced by threat and suppressed by control beliefs | Yanfang Xia

Stress is part of daily life, yet we are not constantly stressed. Why is that? One important factor may be our belief of control – how much we think we can influence the events and outcomes. As illustrated by learned helplessness, control beliefs affect motivation and mood. When people feel they have no control, their responses tend to be stronger. In this project, we use a shock-avoidance learning task to study how control beliefs shape bodily threat responses, such as pupil dilation, heart rate, and skin conductance (implicit sweating). This may help us uncover the cognitive and computational mechanisms that regulate stress and resilience.

Bringing computational psychiatry to clinical practice: Patient stratification for successful administration of intranasal s-ketamine in treatment-resistant depression (ComPass-TRD) | Dirk Geurts

Depression affects millions worldwide. For one in three patients first treatment steps don’t work. A new option for these patients, esketamine nasal spray, can be of help; but it’s expensive, hard to access and is not helpful for everyone.

The current project aims to predict who will and who will not benefit from this treatment. We use cognitive behavioural tasks and advanced computational modelling methods to investigate a personalized estimate for each patient on successful treatment. We use brain imaging to investigate the involved brain networks. This helps to understand and predict esketamine therapeutic effects on depressive symptoms and hopefully will support in the future better treatment strategies for patients with difficult-to-treat depression.